Lalla Essaydi – Education and Family Guide

GRADES 6-12

BACKGROUND

“In my art, I wish to present myself through multiple lenses — as artist, as Moroccan, as traditionalist, as Liberal, as Muslim. In short, I invite viewers to resist stereotypes.”

– Essaydi

Lalla Essaydi is a contemporary American photographer and painter born in Morocco. Creating elaborately staged and layered photographs incorporating traditional Arabic architecture, calligraphy, and henna painting, Essaydi challenges assumptions made about Arab women. The exhibition also explores the lenses through which Westerners view the Middle East, and how that view affects both cultures. The literal and metaphorical layers of Essaydi’s photographs invite reflection as they challenge stereotypes.

VOCABULARY

Orientalism – the imitation or depiction of aspects in the Eastern world, going as far back as the 1400s. These depictions are usually done by writers, designers, and artists from the West and are often found to be problematic due to the patronizing and eroticized style utilized.

Othering – treating people from another group as essentially different from and generally inferior to the group you belong to.

Arab – a cultural and linguistic term referring to those who speak Arabic as their first language.

Stereotype – to form a fixed and often untrue or only partly true idea about a group and that represents an oversimplified opinion, prejudiced attitude, or uncritical judgment

Calligraphy – artistic, stylized, or elegant handwriting or lettering and the art of producing such writing

Henna – a paste made from the powdered leaves of a tropical shrub, used as a dye to color the hair and decorate the body.

Male/female gaze – The “male gaze” invokes the sexual politics of looking and being seen and suggests a sexualized way of looking that empowers men and objectifies women. In the male gaze, a woman is visually positioned as an “object” of heterosexual male desire. The female gaze is a term representing the looking done by the female viewer.

Subvert/subversive – to overthrow, redirect, or destroy the power of something. Subversive art attempts to undermine the dominant values and traditions of a society or common ideal.

Reclaim – to get back something that was lost or taken away, physically or symbolically through action

Photography, Installation, and Performance in Essaydi’s Work

Essaydi’s photographs are technically impressive. Behind each of her images are weeks of preparation, as the text is composed, the fabrics are dyed to match the setting in which they will appear, and the architectural backdrops are carefully constructed. The almost life-size photographs appear in sharp focus, the result of her use of a large-format camera and traditional film.

Essaydi covers her models, and sometimes their garments and walls, in layers of hand-painted henna calligraphy, subverting traditional Muslim gender stereotypes through the presence of the written word. The sacred Islamic art form of calligraphy, traditionally reserved exclusively for men, is used by Essaydi as a small act of defiance against a culture in which women are relegated to the private sphere. Furthermore, by creating this calligraphy with henna, an art traditionally employed by women for women, Essaydi fully reclaims the female voice. The performative process and the resulting photographs allow Essaydi to push and pull the boundaries between East and West, male and female, past and present.

Lalla Essaydi’s photographs often reappropriate and reclaim Orientalist imagery from the Western painting tradition, inviting viewers to reconsider the Orientalist mythology and male gaze on Arab women. Essaydi carefully stages each photograph, posing her subjects to mimic works by French neoclassical painters such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Jean-Léon Gérôme.

“Perhaps by invoking the Orientalist gaze of Western male painters, my work can promote in Western women a greater sense of commonality with their Arab counterparts.”- Essaydi

Henna and Calligraphy – Symbolism and Tradition

The art of Henna—called mehndi in Hindi and Urdu—has been practiced in Pakistan, India, Africa, and the Middle East for over 5,000 years. The art of decorating the hands and feet has been practiced throughout the Arabian Peninsula, the Middle East, India, and North Africa to celebrate significant life events, including marriage.

In Morocco, a wedding celebration can last up to five days and includes time dedicated to applying henna art. Before the wedding ceremony, the bride-to-be gathers with female friends and relatives to eat and talk about married life. The older women pass along their wisdom to help prepare the bride for her wedding night while her hands and feet are decorated with henna. Guests at the wedding also wear henna, but their designs are usually less elaborate than the ones on the bride.

Arabic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy based on the Arabic alphabet. It is known in Arabic as khatt (Arabic: خط), derived from the word ‘line’, ‘design’, or ‘construction’. Kufic is the oldest form of the Arabic script.

From an artistic point of view, Arabic calligraphy has been known and appreciated for its diversity and great potential for development. In fact, it has been linked in the Arabic civilization to various fields such as religion, art, architecture, education and craftsmanship, which in turn, have played an important role in its advancement.

Although most Islamic calligraphy is in Arabic and most Arabic calligraphy is Islamic, the two are not identical. Coptic or other Christian manuscripts in Arabic, for example, have made use of calligraphy. Likewise, there is Islamic calligraphy in Persian or the historic Ottoman language.

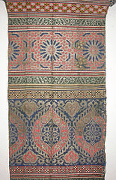

Fiber Arts and History of Morocco and the Middle East

Textiles showcase the artistry of this vast and culturally diverse region. From the intricate embroidery on a Palestinian wedding dress to the complex iconography on an Afghan war rug, textiles reflect the beliefs, practices and experiences of people from these lands.

Gauze, a thin transparent material of silk, linen or cotton, is first mentioned in 1279 under the name gazzatum; it was among the fabrics considered too luxurious for monks to wear. The name may come from the town of Gaza, and the cloth may be of the same type as the famous “veils of Cos” with which Caesar bade Cleopatra cover herself when she visited Rome in 43 B.C.

Muslin takes its name from Mosul, in Iraq, where it was originally made. According to Marco Polo, it was “a cloth of silk and gold,” although the name has, for several centuries now, simply designated a fine cotton or silk material.

Links for more information:

https://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/fabrics-fibers/middle-eastern-textiles [4]

https://study.com/academy/lesson/moroccan-textiles-history.html [5]

More from the Artist:

Feminist Artist Statement- http://lallaessaydi.com [8]

The traditions of Islam exist within spatial boundaries. The presence of men defines public space, the streets, the meeting places. Women are confined to private spaces, the architecture of the homes. In these photographs, I am constraining women within space, confining them to their “proper” place, a place bounded by walls and controlled by men. Their confinement is a decorative one. The women, then, become literal with this visual confinement, I recall literal confinements. The house in the photographs is a large, unoccupied house belonging to my extended family. When a young woman disobeyed, stepped outside the permissible space, she was sent to this house. Accompanied by servants, but spoken to by no one, she would spend a month alone. In this silence, women can only be confined visions of femininity. In photographing women inscribed with henna, I emphasize their decorative role, but subvert the silence of confinement. These women “speak” visually to the house and to each other, creating a space that is both hierarchical and fluid. Furthermore, the calligraphic writing, a sacred Islamic art form, inaccessible to women, constitutes an act of rebellion. Applying such writing in henna, a form of adornment considered “women’s work,” further underscores the subversiveness of the act. In this way, the calligraphy in the images is one of a number of visual signs that carry a double meaning. As an artist now living in the West, I have become aware of another space, besides the house of my girlhood, an interior space, one of “converging territories.” I will always carry that house within me, but my current life has added other dimensions. There is the very different space I inhabit in the West, a space of independence and mobility. It is from there that I can return to the landscape of my childhood in Morocco and consider these spaces with detachment and new understanding. When I look at these spaces now, I see two cultures that have shaped me and that are distorted when looked at through the “Orientalist” lens of the West. Thus, the text in these images is partly autobiographical. In it, I speak of my thoughts and experiences directly, both as a woman caught somewhere between past and present, as well as between “East” and “West,” and as an artist, exploring the language in which to “speak” from this uncertain space.